Generally, I facilitate experiential workshops on topics like senses and emotions in design for conferences and organisations. Being together, working closely is crucial. That all stopped suddenly in March 2020.

I needed both some income and some idea of how to work in a future where in-person workshops were few and far apart (in all ways).

Online was clearly the only opportunity but there seemed to be multiple problems with the delivery technology and the general sense of how online time is spent.

I developed and ran a workshop on Design for Dissent. This was drawn out of the final conference talk I did on Post Normal Service Design and previous workshops on Active and Structured Listening methods. I ran the workshops three times in two iterations.

This post is about what I learnt and uses data drawn from them.

Planning for Synchronous/Asynchronous

What I lost in holding physical workshops is a place but what I gained is time.

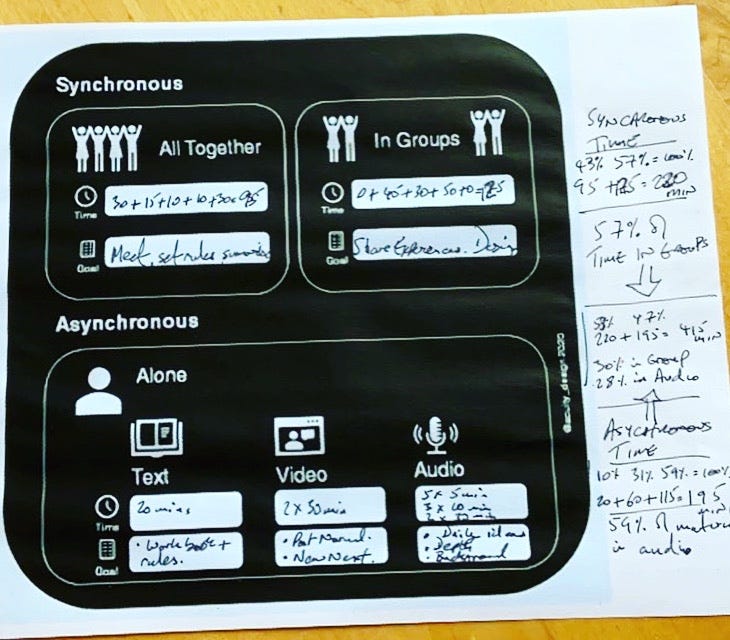

The Design for Dissent workshops ran in a series of 5 days of online sessions. This was the Synchronous time.

Alongside that was the Asynchronous time. This was material for participants to use when they wanted. This included subtitled PowerPoint talks, a 16 page workbook and about 10 different audio packages (from relevant radio documentaries, thru daily podcasts to specialist talks).

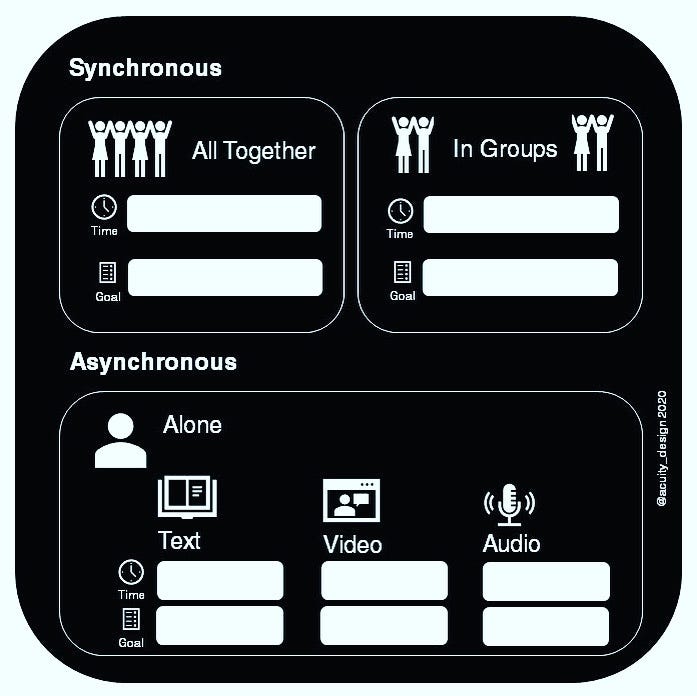

The diagram above is a way of thinking about how to split time and materials synchronously and asynchronously.

I have used it to review how time and materials ended up being used in the 3 Design For Dissent workshop series.

That looks like this in an Excel spreadsheet pie chart.

It can be summarised in this infographic.

Three main points:

- 50:50 split of Synchronous:Asynchronous

- 60% of time online in small groups

- 60% of time offline delivered in audio packages

This section talked about the time split and it’s interesting that a 50:50 split came up.

I will just explain the other two points next.

Together, too many?

Online time together is valuable but the tools (Zoom, Teams, etc) are terrible. They confuse the technical sense of being together (all those faces looking out from tiny rectangles, observing you) with the social sense of being together (next to a person, around a table or facing a whiteboard).

Online time must be planned to minimise stress and maximise social value.

Most video conferencing systems are designed to privilege speaking and a single speaker in particular. They are lecture-based systems. They are not well designed for group chats and not well designed for active listening.

Offline lectures help minimise the wasted time of being together listening to a teacher. It is not a comfortable space and online exaggerates the social discomforts (drawn from school and college experiences).

All together in a big group leads rapidly to the problems of online meeting stress. Being observed by so many people is not natural and creates terrible pressure. Being observed by many faces (all looking slightly bored or somehow annoyed) is something that any public speaker or facilitator knows and it deeply uncomfortable. Most people do not experience it and it’s a horrible feeling as you use up your own internal resources to rebalance the apparent social deficit.

Switching off cameras helps.

Switching to small groups helps most.

Small groups and explicitly talking to people about imagining they are together as a cluster. Breaking the rectangles. This is why 60% of online time spent together in small groups matters.

However, the need here is to facilitate the workshop strongly so people can work together without you.

I didn’t use online collaboration tools like Miro because they replicate a form of physical workshop I don’t use. They look interesting as a space between people tho.

I did use a mix of other media tho: video, text and audio.

Listening more

The other result was the use of more audio packages, like podcasts, for 60% of the workshop media.

I have delivered a few online conference talks: both live (thru Zoom) and recorded (PowerPoint plus iPhone footage).

Video is hard. Both, for me, in ‘good’ production terms and, for participants, in the effort needed to concentrate. It requires everyone to sit down and face a screen and that’s not great when everyone is tired of facing screens.

Text and printed media are great but, problematically, it’s hard to send workshop materials like booklets and cards to people reliably at the moment. The workshop workbook ended up as a PDF but I ended up sharing it as a download. The postal system is currently untrustworthy (internationally especially: I checked on actual delivery times to US and Australia) and you cannot know if a person has access to a printer. A digital text is nice but again: more screen time.

Audio is good (tho with text as alternative format) as it doesn’t tie a person to a place or a time. Podcasts (say 5–10 minutes) can be listened to where and when a person likes and they can do other things at the same time.

60% of the workshop media was audio because it had the best balance of, for me, production effort (listening and editing your own voice is painful but necessary) and, for participants, value in their experience of the workshop series.

Learning for the future

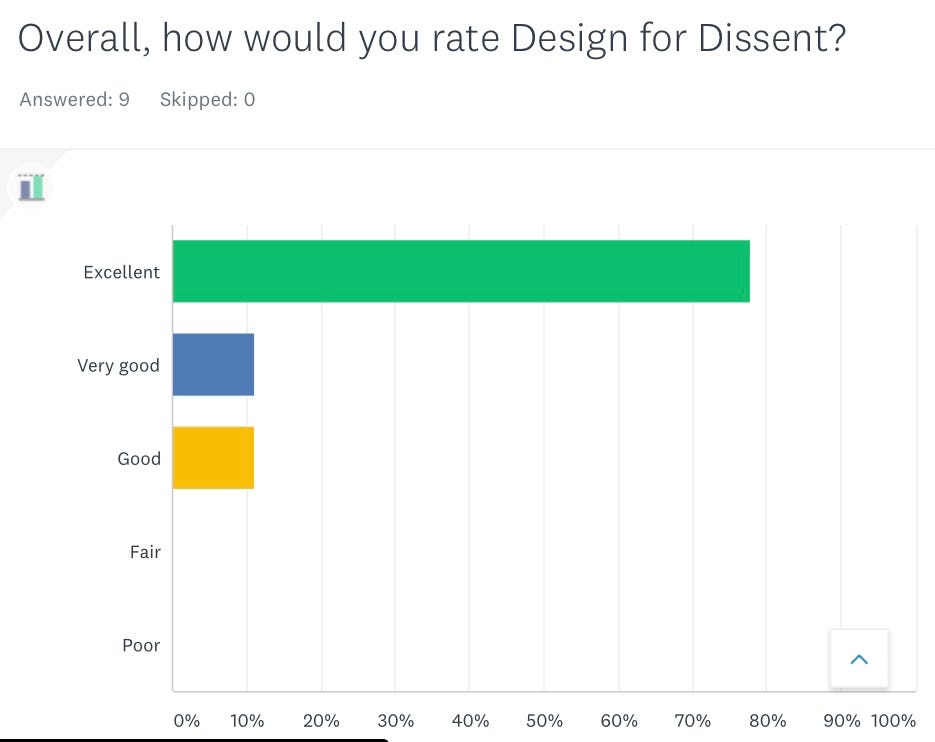

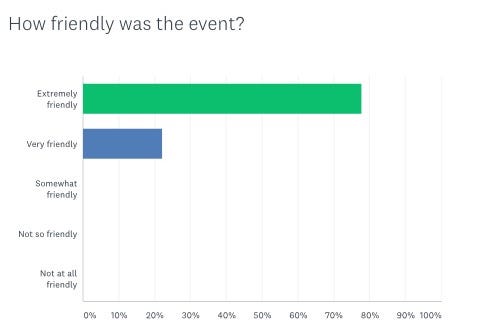

Design for Dissent workshops had good feedback from participants.

Also they were viewed as friendly (which is good, given the stress of online workshops).

For future workshops, I plan to keep using the three ideas of 50:50 time split, 60% small online groups and 60% audio media. As I do more, I’ll get more data and more feedback. For now, this is a good foundation for working in a new way that has suddenly become necessary.

You can download this workshop planning canvas for free from Dropbox: Online Workshop Planning Canvas A4 in pdf format.