Post originally written 27th April

The Hero is an important character in stories. Storytelling is now recognised as meaningful to communication to all kinds of audiences. This post is about its meaning in organisations and with staff. I am designing a workshop at the moment on divergence and dissent and these are notes from work on an exercise on enabling more dissent.

In both politics and business, leaders can be seen as heroes. At companies like WeWork and Theranos, the founder was lauded and followed as a hero. Yet they failed and so many people were dragged down along with them.

Knowing that there are both brave and tragic heroes can help break this trap. This post is about what heroes are and how they differ.

The Hero, the journey

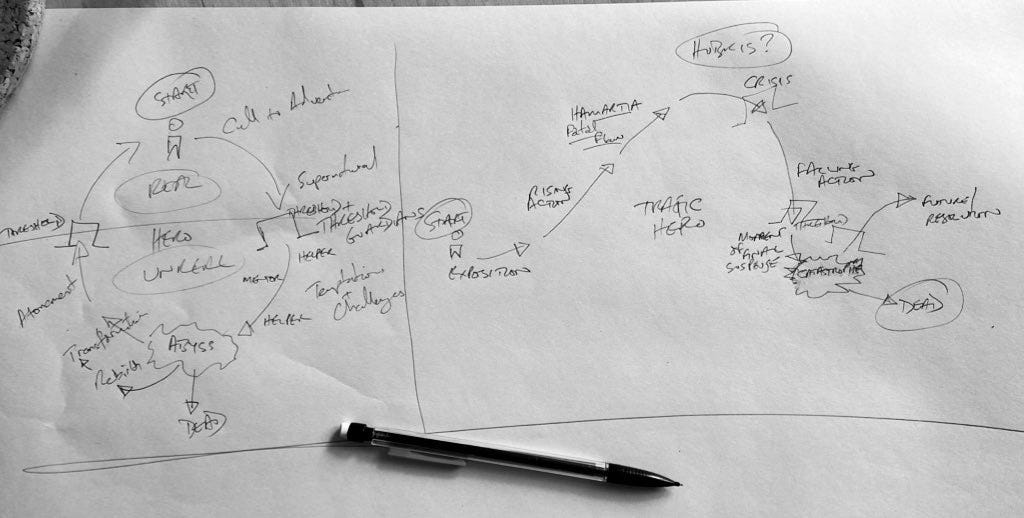

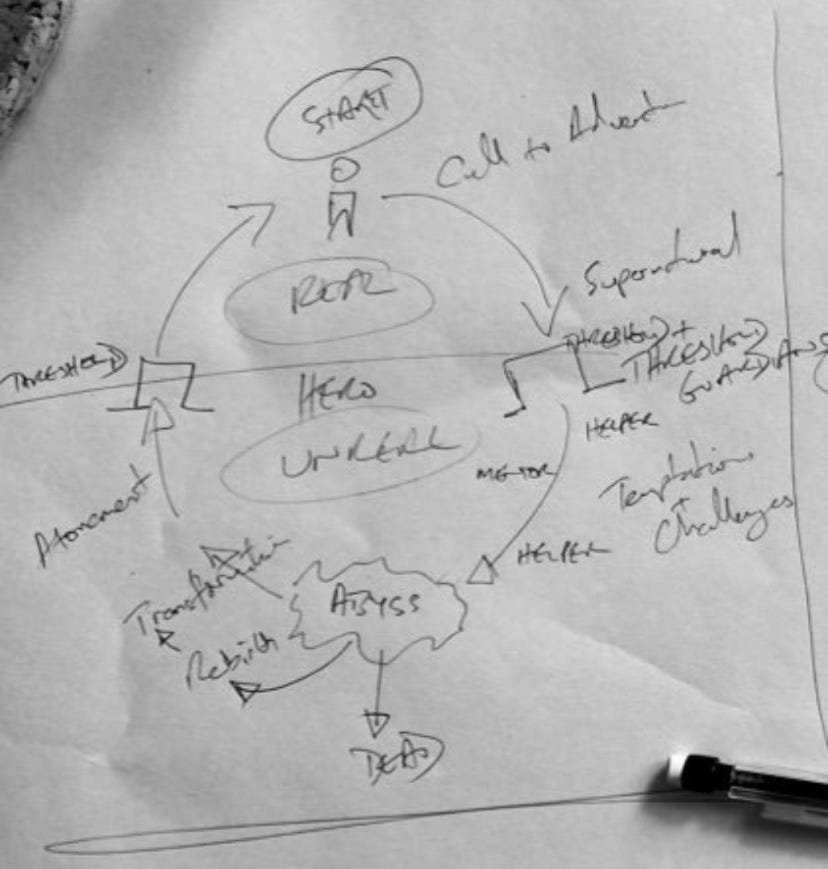

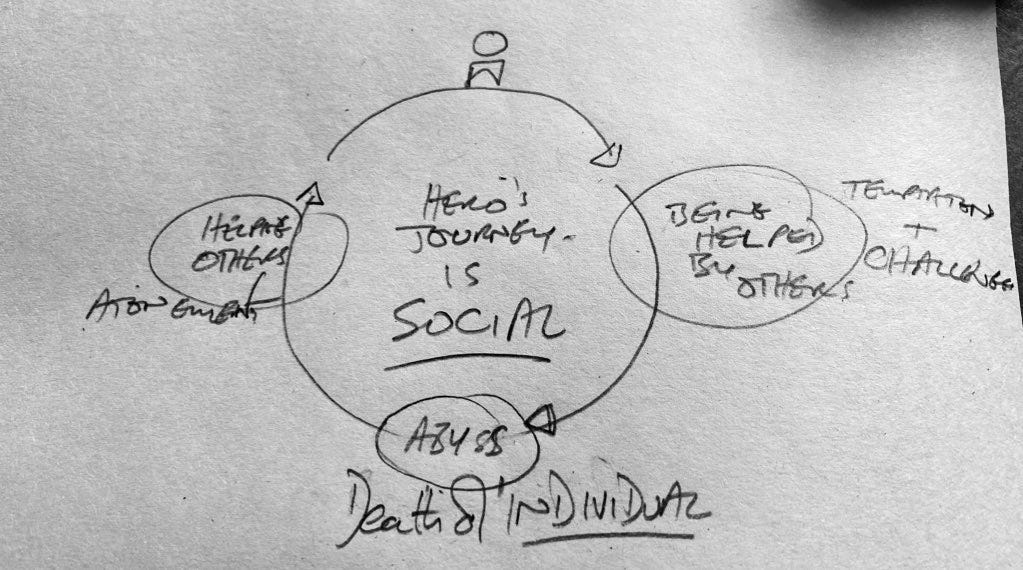

Campbell’s Hero’s Journey is used a lot in narrative design. It’s a cycle of personal change. A journey of transformation.

The use of movement is very good. Humans have been moving and changing for centuries. The cycle seems a bit odd tho’ – returning to the same place the hero started out from.

The journey passed thru thresholds into a supernatural world where the hero encounters helpers and a mentor. There are challenges and temptations.

All leading to the Abyss. The moment of an absolute test. This transforms the hero (or kills them).

After this moment, the hero is transformed and atones for his failures prior to the Abyss. The hero helps and enables the lives of others.

Finally, the hero returns (as it is circular journey) to home.

This journey and its narrative structure is used in storytelling. However, it’s all very positive. There are places in the story that failure is possible but the momentum (inertia?) is towards success and positive transformation.

The problem is that organisations are not full of selfless heroes like this.

To hold up this ideal narrative to people is foolish.

Firstly, it creates a pressure on them to act (and maybe fail) in ways that may not match the way the organisation around them operates.

Secondly, what if there is another kind of hero?

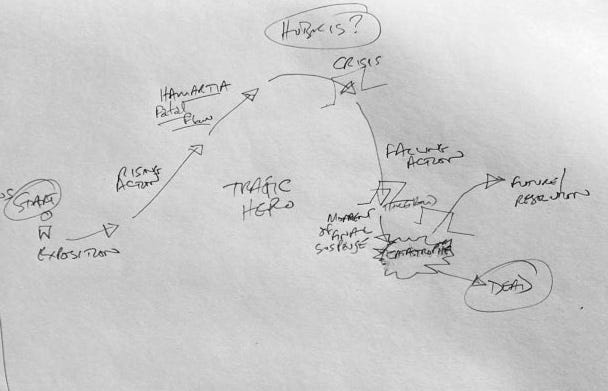

The Tragic Hero

It was Shakespeare’s birthday last week. I watched a production of Macbeth online as well as some of The Tempest.

Macbeth is a hero. He is a tragic hero.

There is a hero’s journey but it is different.

This hero becomes stronger thru the journey but there is a problem.

The hero is flawed.

Hamartia.

The fatal flaw.

A strength that is a weakness. A piece of knowledge unknown to them. An element of personal character that is too much or too little.

The journey is moving towards a moment where this flaw is shown up in a crisis.

Then the hero falls.

Falling towards a catastrophe. A moment of final suspense. A battle that the hero will lose.

The hero dies.

The story is resolved. The journey ends. Yet the hero is not there. It is other people who live on and create a better world.

The shadow of the Tragic Hero’s journey is helpful when talking about organisations.

It is important to understand that you might be the Tragic Hero. You are flawed in a way that will lead to your failure.

It is also important to realise that someone else might be the Tragic Hero and their actions (heroic and notable as they may appear) are heading towards a failure that may lead to their personal catastrophe. More importantly, that personal catastrophe may have negative consequences for all those people around them at that time. The followers, the team mates, the staff: all of them will be hit by the shrapnel of the final catastrophe. The tragic hero destroys those close to them.

Knowing that hero’s journeys are both positive and negative can help provide a greater space for people to understand how to act and what to learn.

The crucial difference

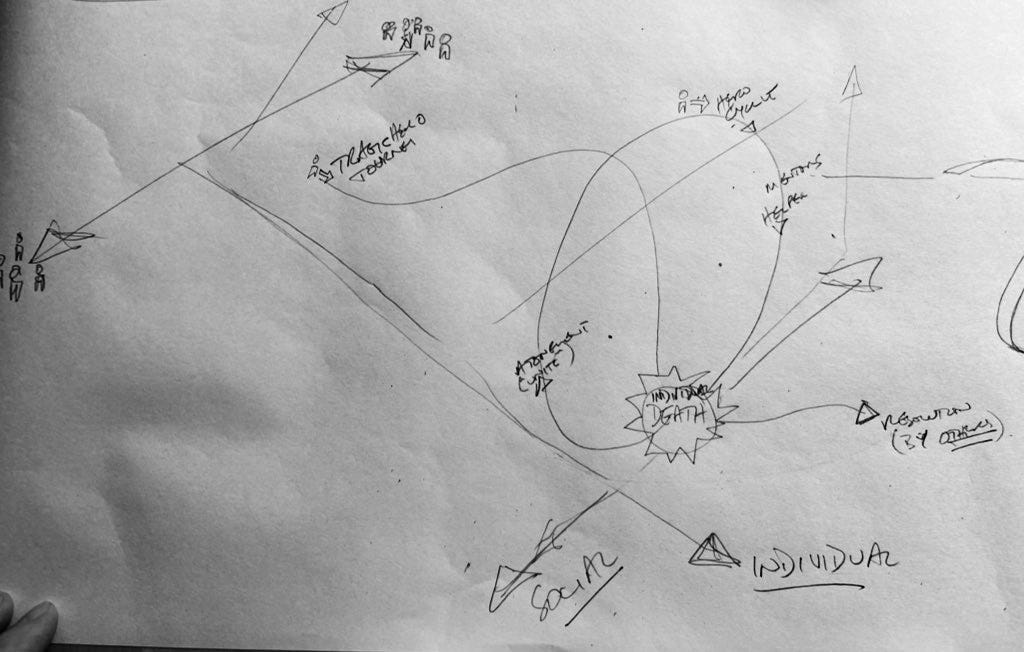

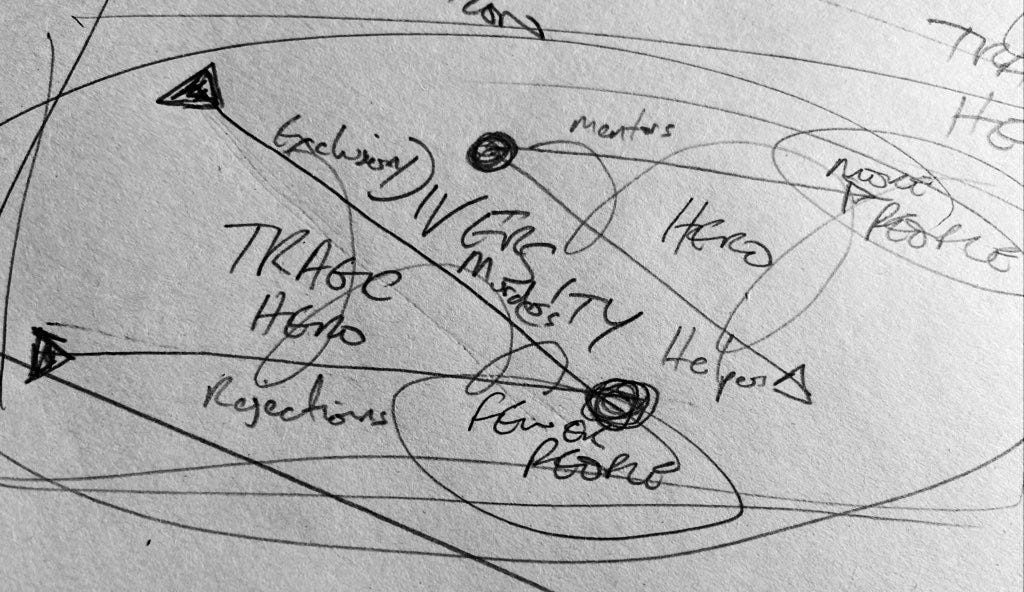

I tried to overlay the two journeys to understand where they meet up and where they divert.

Both journeys have a moment of Abyss or Catastrophe. A moment of death (final for the tragic hero) and rebirth (transformation for the hero).

More noticeable is something to do with community.

The hero travels and meets helpers and a mentor (generally one but it can be a range of characters teaching specific lessons).

The hero is transformed and atones. The word ‘atone’ comes from Latin for ‘to unite’. The hero acts to help others, be part of a community to enable positive change for all.

The tragic hero’s journey is one of cutting away social connections. The tragic hero is heading towards a battle they fight alone (even if they drag in others as peripheral actors).

The hero builds outwards, towards strength in learning from and being part of a community.

The tragic hero closes in, ignoring the words of others, believing in their strength alone.

One journey becomes wider. One journey becomes narrower.

Both are about diversity.

Success thru it. Failure by rejecting it.

Asking for help, offering help

The hero asks for help and use that experience to offer help.

This seems to be the way of testing what kind of journey you, or a manager or colleague, are on.

- Are you asking for help?

- Are you offering help?

The flaw seems to be in belief that individual skill or capacity is the route to success.

Organisations recruit and manage staff on an individual strength basis. The organisation cannot tell who are Campbell heroes and who are tragic heroes and thus cannot tell if it is heading towards catastrophe.

A system of recruitment and promotion that recognises the relationships of a person, rather than their capacities, might be beneficial. The hero is made by their ability to learn from others and help others. It’s not their capacity that matters but their openness to be helped and help.

We can be heroes when we ask for help and offer help.

This is what organisations need to support.