Listening is a skill that is disregarded too much in a modern society that thinks speaking is paramount.

I ran a workshop at EuroIA18 on structured conversation and listening. The workshop changed radically in terms of content due to counselling training I received. The professional counsellor’s view on sympathy and listening was very different to what I imagined.

This post is a short story about some key points. It’s easy to read this and think you understand but the hard part is being in a workshop practicing the skills.

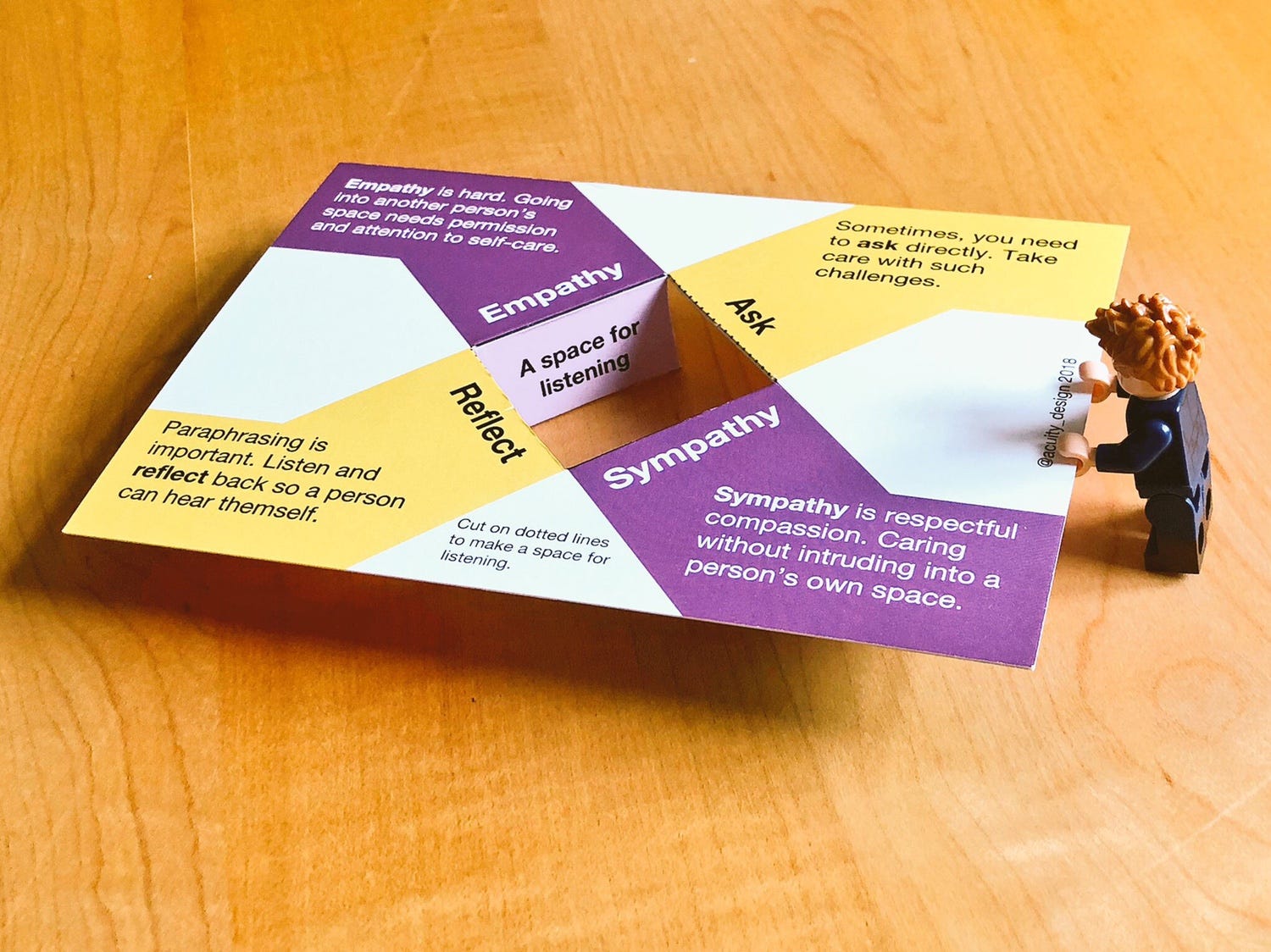

Making a space for listening

To listen, you need to make a place to be heard.

Deliberately saying that you will listen at a time and a place is important.

This is their space. You hold it for them but they own that space – in time, in place.

Being sympathetic

You are outside their space but you can be sympathetic. Being next to them, sharing that time and place shows you care.

You cannot know the experiences that are inside them. You may have similar’ish experience but they are not the same. You can be sympathetic.

Reflection

Having a space for listening is not just about you. It’s centered around the person.

Paraphrasing and reflecting back the words they say when you are listening is valuable. Not just to your understanding but to them.

Hearing yourself and listening to your words and ideas is a part of a space for listening. Another person valuing your speech and helping you listen to yourself.

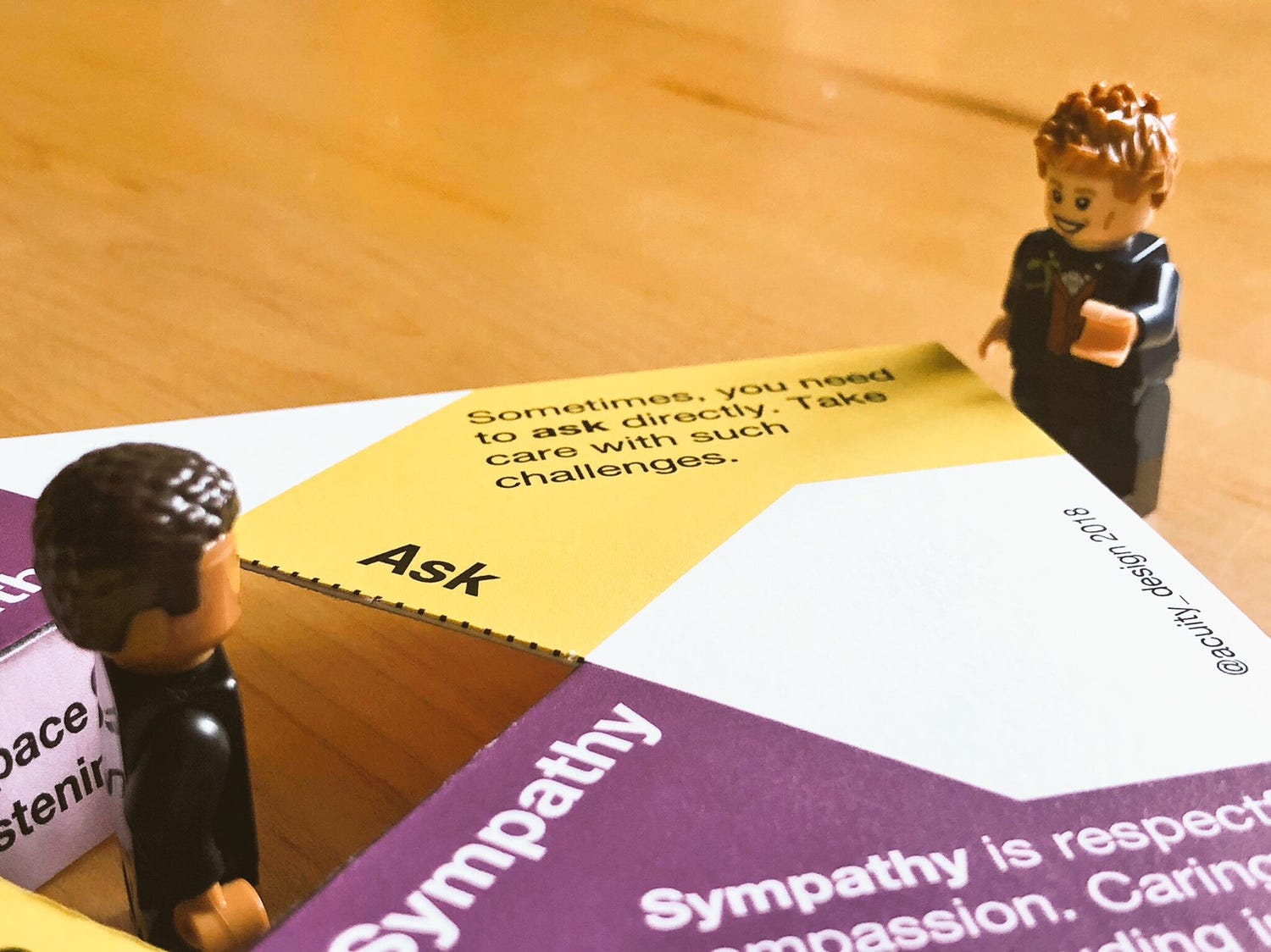

Asking

Asking direct questions (whether open or closed) is an act that can help clarify the unsaid words.

It is breaking thru the idea that the space is for them to talk and you to listen. You are crossing a liminal. You need to ask respectfully and know that it is an intrusion.

Empathy

Empathy is aligning yourself with the experiences of another person. This has consequences.

Firstly, it is hard to do. Both in aligning yourself with experiences that you may never have had*(see footnote) and in the cognitive effort to hold that state.

Self care is a big question before being empathetic.

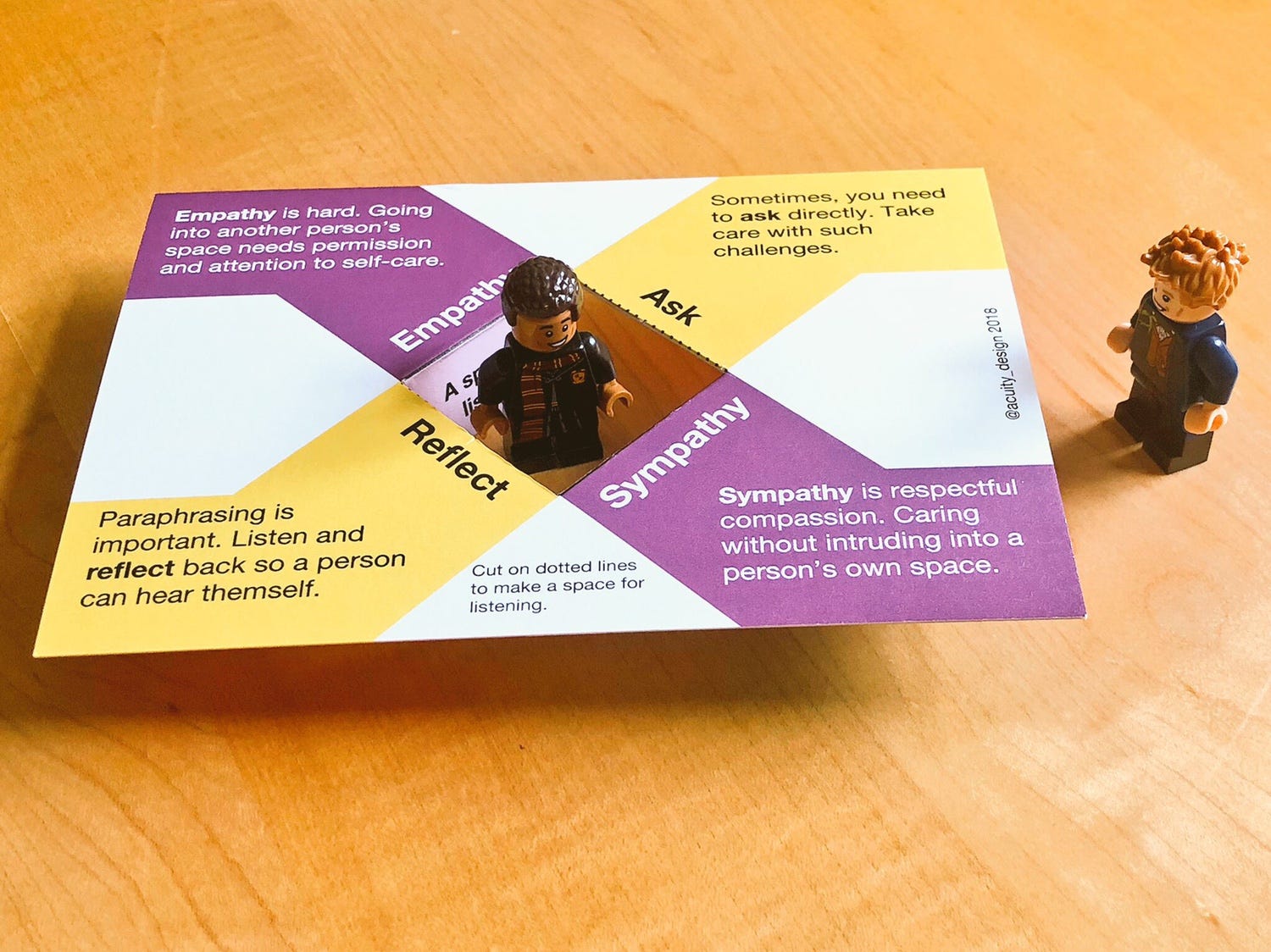

Entering their space

Empathy means entering that space for listening that you made, that you held for someone else.

You are intruding. You need to be absolutely sure that you were invited.

Your stories, your personal luggage

We share stories. We talk and we listen. That we don’t listen enough is the main point of this post.

Entering another person’s space and being empathetic has a habit of people sharing their own stories of experiences. This is known as the Identification problem: someone describes their experience, there is a moment of silence hanging between you and then you blurt out a story about how something like that happened to you. This is not empathy, it is identification.

Worse still, you cannot take it back.

Even when you leave – which you must – your personal luggage remains in their space.

Empathy has consequences for both people. Use it but understand its effects.

Holding a space for listening

Finally, it’s all about the value of holding that space for someone and listening actively to them.

- You need to be sympathetic or else the person will be alone

- You can be reflective so a person can listen to themself

- You can carefully ask questions to help uncover unspoken words

- You can use empathy but be aware of its consequences

*Footnote on Empathy and Experiences

This post was written in 2018 and this footnote is from 2020. Lots of things have changed but there is quite a big bias on my part at this point in the post that needs discussing in more depth.

This post assumes empathy is hard because it presumes that the professional who is listening is not of the same community as the person who is speaking.

Just this month I have come across two people discussing the problem with that presumption. First in Cormac Russell’s Rekindling Democracy. Second in Alex Haagaard’s interventions in the #DisabilityInUX online event organised by Twitter.

Both of these people reflect on how empathy is offered as a professional tool because the designers and the users are presumed to not be of the same community or have the same lived experiences.

In this original post, my problem with empathy is because I too presume that lack of crossover. I just need to make sure that this is a bias in my part.

Both Cormac (in a sense that neighbourhood’s can provide empathy because people do share experiences) and Alex (in talking of disabled people, in design teams, as professional designers who can be empathetic) are speaking of empathy where alignment of lived experiences does exist. This is something that needs to happen more. Placing design at a neighbourhood level by people with shared knowledge of problems rather than as an intervention by institutions (as discussed in Cormac Russell’s new book). Placing lived experience in professional design by removing the bias that designers and users are not the same thing (in Alex Haagaard’s terms) thru recruitment, retention and promotion of disabled people.